This is the fourth in the series of three posts exploring digital technologies and their potential use in heritage organisations and museums with limited funds but maximum enthusiasm.

In this post, we’re using 3D in another way: presenting objects and evoking their past significance – virtually.

Aura, and why it’s not just about touch:

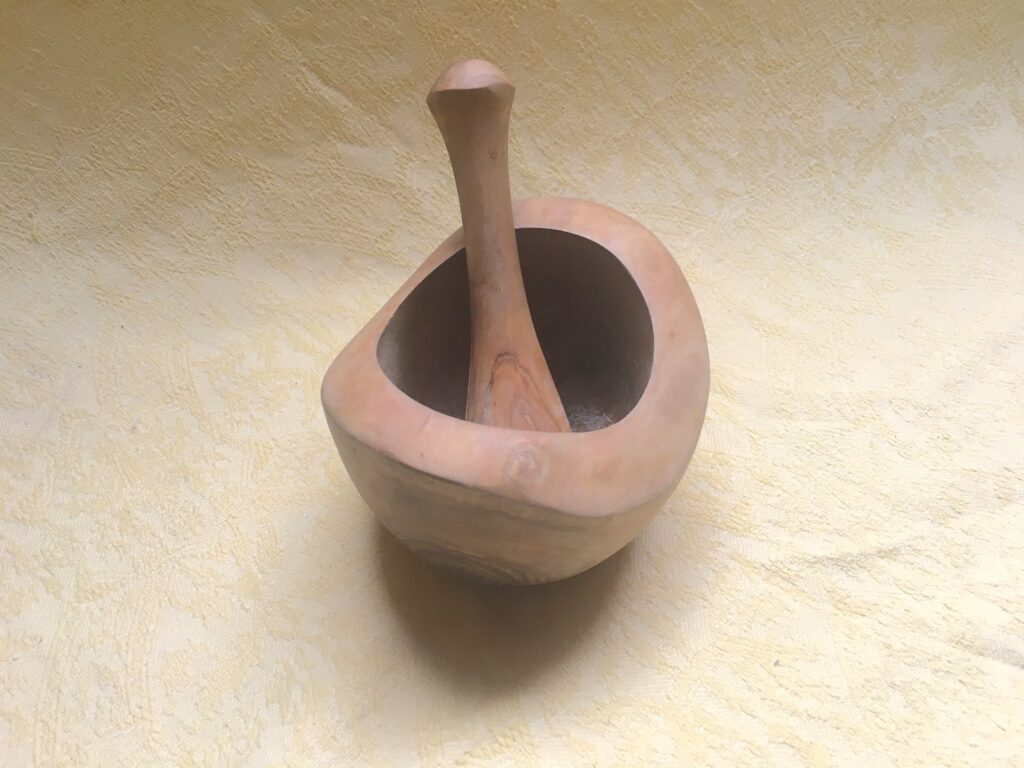

Here’s my pestle and mortar.

I use it in my kitchen. I cook with love for my friends and my family. Right now, with it in my hands, there’s this spirit-lifting joy of crunching up fennel seeds and getting that concentrated earthy, celery smell. Winter stew; a table, people to love. Warmth. Wine.

It’s lovely to hold. It feels reassuringly solid in the hands; unexpectedly smooth and cool, because the wood is so dense.

In decades to come, maybe some future historian will examine it. It’s a humble utensil; form unchanged through centuries; incongruous these days, in a setting of juicers and coffee pods and my use of it elevated from the prosaic to the almost ritual. Respect goes to any curator who can get across how important and centering this artefact is to this 21st century human.

We often talk of artefacts and their aura. The act of feeling the heft of an object in the hands activating empathy for those who held it before. Maybe the future historian will feel that empathy and maybe not judge us too harshly.

Aura as place

But, having opportunity for such intimate access as to touch an historic artefact is a rarity. Visitors to museums do so in the most restricted of circumstances, and often having travelled for hours. When they arrive it’s merely to be in the same space, separated by a rope or a glass pane. That’s a big ask for an aura. Inevitable then that the big institutions – inheriting buildings built for spectacle – command the lion’s share of people willing and able to make the physical effort. They reward them with sheer atmosphere – cathedrals to history. Heritage sites go one better, of course: the entire site is an artefact and that’s the aura the visitors feel.

Aura of story

When museums talk about ‘bringing the past alive’, maybe it’s a sort of covenant – if we provide enough imagery, sound and story, our visitors won’t be disappointed not to be able to touch. The aura of the artefact is kindled another way.

Aura online?

With footfall at its lowest ever, thanks to the recent pandemic, exhibitions are moving online. The same imagery, sound and storytelling is still being used to provide compelling context, except that now the audience and artefacts are separated entirely – by a screen. Of course they should be encouraged to return in their droves to engage and have the conversations and interactions with the knowledgeable, passionate and approachable people who often volunteer as staff, but the interactions with the artefacts? It can be argued that online is a very good option. Indeed, it may be even an opportunity.

Presentation for all.

It’s not just big museums who can provide this sort of sophisticated representation. These abilities are within reach and at very low cost.

Back to the pestle and mortar. There’s already a story, about the feel of it and some guff about pining for simpler times – ha! dream on – and there’s a picture. So far, so display-panel. Let’s add some more flavour, using a technology called photogrammetry:

… and using sound, we can give you a feel for its ‘heft’…

… finally, you can see the context in which it’s used – it’s a 360 view, so look around …

… and see outside…

…learning so much more about its place.

All good stuff, but importantly, we’re creating rewarding, immersive content at low cost – it’s available with the use of a mobile phone, some free software and a few hours to produce (mostly waiting for the computer to crunch the 3d model together).

Benefits of being online

What can be done with these representations, once they have been created? How do we get them in front of an audience? And if the audience isn’t going to a physical museum, how do we get the donations to pay for the upkeep?

There are 4 important parts to a really fantastic incentive for museums to put their artefacts online:

First is Ease of creation. Photogrammetry is a way of scanning artefacts to produce 3D models, and relies on taking a number of photos around an object, and using a computer to extract the features. There are a couple of stand-out software products to use, along with a fairly good camera (the one on a mid-range smartphone is plenty), and a light tent to make sure the object is evenly lit. Agisoft Metashape is around £150, and Meshroom is Open Source and free. Both have a fantastic community of supporters and there are many videos which will help with the initial learning curve.

Next is Free Storage. Somewhere to put scanned artefacts where they can be seen. SketchFab is a good example. Born in 2012 as part of a French startup programme, its service is now the de-facto place to store and share 3D models and patronised by organisations such as the British Museum and the Louvre. It has a thriving community of people who take advantage of its free storage, in exchange for creative commons licensing on uploaded models.

Third, there’s Incredible Reach. The obvious point to make is that over four and a half billion people connect to the internet globally, in ways which are nearly instant. In Britain, depending on where you are there can be a million people within an hour’s travelling of a venue (and if they all turned up, the cafe would be a little congested). There are now a number of services which exist primarily to aggregate and publish collections, media and stories for museums and other institutions. They do two things: first they provide a nice framework – think of it as the building and presentation equipment to show your artefacts and their supporting information. Second, they apply the same technologies as search engines and social media outlets to find and present items of interest – ‘Surfacing’.

The thing to remember here, is that they house and present your content; you still need to create it – but you don’t need to go through the hassle of creating a website, paying for its hosting and working out how it’s going to play nicely with search-engines, so people can find it.

The publishers listed here are not exhaustive – we’ve just tried to give a taster to show what’s out there. What’s notable of these below is that they are all funded. There is no cost to the institution. Off we go:

Google Arts and Culture is the biggest player here and, given the ability of its parent company Alphabet to pick a winner, it’s pretty clear it’s going to be around looking after your virtual content for a long time to come. It’s a non-profit initiative, and works globally to aggregate and publish the work of partner institutions – no matter how small.

Perhaps less well known to the mainstream audience, Europeana has been quietly getting on with its mission, to digitally publish European culture for all since 2005. Not surprisingly it has partnered Google’s global initiative. Publishing on Europeana needs to go through an aggregator service. It’s still open to UK submissions, even after, er. You Know What.

Aggregators provide added value, and work with institutions in a number of different ways. Some provide a service with a particular specialism, such as archaeology. Of particular value here is Share3D, which is a platform provided by a non-profit consortium, co-funded by Connecting Europe Facility of the European Union, as part of the 2018 European Year of Cultural Heritage. Its technical driver is the aggregator Carare. The platform provides the tools necessary to put together a story presentation, associated with a scanned 3D artefact, hosted on Sketchfab. The whole thing is then submitted to Europeana automatically.

Museum Crush is a similar UK initiative. It’s the product of Culture24, who are an Arts Council funded Sector Support Organisation. They do a lot of good stuff.

Fourth, it’s Another Way to Increase Revenue. Always a ticklish subject and there is a lot of good advice out there to institutions, as to how to persuade visitors to part with cash, and the mechanisms to do this. There’s a sting in the tail here, too. None of publishers above support payment mechanisms in their platforms, although they can link the visitor to an institution’s webpage, for example. If you’re in the UK and running a not-for-profit, you need to take a look at the National Funding Scheme’s, Donate! facility. It has the great advantage that it can be reached from a publisher, website, or even text message. For a great example, head on over to the Thackray Museum of Medicine, based in Sheffield, UK.

Last word

That about wraps it up, apart from two last things:

A note of caution – given to me by Ruth, Interpretation Advisor: Plan. If each artefact needs scanning and needs a story, that’s a ton of work. Ensure you have a path to follow which begins with scanning only the essential pieces and which protects their virtual counterparts, even if it’s just keeping their files safe on a memory stick in a fire safe.

And finally an exhortation.

According to a survey by Museum Booster in 2021, of 150 museums surveyed only 6 managed to stay open during the pandemic.

However, only 28% of the respondents managed to design new digital revenue sources

and still 50% of the respondents do not have their own digital team or relevant

department.

Get your stories out there. It’s about as easy as it can get, now, and about as cheap as it can get. Just think:

4.64 Billion

bums

on seats!

This was the (bonus) fourth post in the series of three – for more time-sink opportunities, look no further than:

Digital for Museums and Heritage 1: 360 Tours